Published in the CHAPCA newsletter Trendsetter, February 2015

What would the US medical system be like if physicians were as well trained in the human aspects of patient care as they are in the technical aspects of medicine? In a recent article published in The Atlantic, James Hamblin highlights the work that Atul Gawande and Angelo Volandes are doing to raise awareness of end-of-life issues, and the important role that physicians can play in fostering healthy end-of-life conversations.

Did you know that the human brain shrinks as we age? “At 30 years old, a person’s brain weighs about three pounds. In its capaciousness it wears the skull like a well-tailored suit.” By age 70, however, there is usually around an inch of space between the brain and the skull! While this loss of brain matter doesn’t necessarily mean that the aging are any less “brilliant,” it is an example of how the body slowly wears down – losing mass and resiliency – as we age.

Atul Gawande, author “Being Mortal,” which was published this past October, says that doctors are trained to resist and fight this process, treating the process of aging as a battle to be fought, rather than a natural progression to be understood and planned for. Of course, if old age is a war, nobody ever emerges victorious. Death always has its way in the end.

Atul Gawande, author “Being Mortal,” which was published this past October, says that doctors are trained to resist and fight this process, treating the process of aging as a battle to be fought, rather than a natural progression to be understood and planned for. Of course, if old age is a war, nobody ever emerges victorious. Death always has its way in the end.

In Gawande’s view, death is simply not discussed often and openly enough in American society. Death is shunned and denied, rather than openly discussed and accepted. Patients often suffer agony at the hands of well-meaning doctors who have been trained to see death as the greatest evil that can befall their patients, failing to perceive that there are fates worse than death.

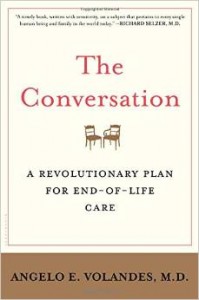

Harvard physician Angelo Volandes has recently come out with his own book, which is in many ways complementary to Gawande’s. In “The Conversation,” Volandes delivers a wake up call to a country where far too many are receiving care that they did not ask for and do not desire. “I think too many people don’t know what’s going on behind those closed doors in hospitals,” he says. “But if they did, they’d be outraged. So many people are getting – not costly care – I’m talking about unwanted care.”

Harvard physician Angelo Volandes has recently come out with his own book, which is in many ways complementary to Gawande’s. In “The Conversation,” Volandes delivers a wake up call to a country where far too many are receiving care that they did not ask for and do not desire. “I think too many people don’t know what’s going on behind those closed doors in hospitals,” he says. “But if they did, they’d be outraged. So many people are getting – not costly care – I’m talking about unwanted care.”

Much of this stems from a lack of real conversations about what patients want at the end-of-life. These conversations often never occur because physicians are not taught how, when, and why to have them. Dr. Volandes points out that, in order to become a board-certified physician in his residency training at the University of Pennsylvania, “I was required to prove my competence with inserting central line catheters, leading Code Blues, performing lumbar punctures, drawing blood, and obtaining arterial blood-gas samples. But not a single senior physician needed to certify that I could actually speak to patients about medical care.”

Volandes sees his book as a sort of “part two” to Gawande’s. In it, he “goes an extra step to tell people exactly how to raise the subject of death – in a context of personal values and life priorities – with their doctors.” At this point, he says, training patients to initiate these conversations is critical. If a patient doesn’t start the conversation, it is unlikely to happen at all.

Rather than “die fighting,” both Gawande and Volandes are urging Americans to re-embrace the more gentle ways of dying that were more prevalent only a few generations ago. Gawande points out that in the 1940s almost everyone died at home. By the late 1980s, only 17% did. “This shift was partly due to tremendous scientific advances that transformed the hospital from a place of very few effective treatments, to a place that had intravenous antibiotics, heart surgery, and kidney transplantation. By the latter part of the century, a doctor could do something for almost anyone.”

In an age of powerful modern medicine, the question is no longer simply whether someone can be kept alive, but also what conditions the individual will experience while still living. At what point is allowing death preferable to the “life-saving” alternative? When are health care providers missing the point altogether? Is there a point at which medical care becomes torture?

The tide is beginning to turn on the way people die in America. By 2010, 45% of Americans were dying in hospice care – which for the most part meant a home death. Gawande calls this a “monumental transformation” in just a couple of decades of the way dying happens in America. Nevertheless, the work of change is far from over. “We have begun rejecting the institutionalized version of aging and death, but we have not yet established our new norm.” (The Atlantic, 1/25, www.theatlantic.com/health/ archive/2015/01/dying-better/384626/)